Research Report

Convenience Industry Action Plan for Becoming an Employer of Choice

Convenience store operators are constantly challenged to both attract and retain frontline staffers. This new action plan from the Coca‑Cola Retailing Research Council for convenience stores examines the causes of this problem and outlines potential action steps for individual managers, companies and even the entire industry.

Executive Summary

Context

Convenience stores are finding it increasingly difficult to attract and retain the right frontline staff, as the industry grows, and product and service offerings become more sophisticated. The recruitment challenges and high turnover pose a threat to revenues from understaffed stores and negative customer experiences, and they generate additional costs for onboarding and retraining. The results can be hindrances to store operations and challenges to growth across the industry.

Now is the time to act. There is much to celebrate in the industry’s past adaptations to societal changes, and it is in a good position to meet this latest challenge. The staff shortages result, in part, from the industry’s success. As stores evolve, frontline roles are becoming busier and more complex, while sales growth over the past few years has increased demand for staff. The growth has been accompanied by higher margins and has strengthened the industry’s finances, so companies currently have the resources to make changes.

The Coca‑Cola Retailing Research Council North America NACS (NCCRRC) believes that addressing the impediments that stand in the way of the industry being viewed as an employer of choice is a collective responsibility that must be addressed by the industry. But it also requires action by individual managers and companies to improve the workplace experience and their approaches to the acquisition, development, and retention of talent.

The NCCRRC has developed a Convenience Industry Action Plan based on insights gathered from industry experts and direct input from frontline employees — past, present, and potential. The research consists of both quantitative surveys and qualitative focus groups. It was designed to better understand both the perceptions and realities of frontline labor, and to develop industry-specific solutions that can mitigate these challenges effectively.

Current State

The research found that a vast majority of people have no desire to join the industry, greatly limiting the available talent pipeline for convenience retailers. Frontline workers signaled competitive compensation, affordable transportation, schedule flexibility, and personal safety as the most critical factors in their desire to work in convenience. The workplace experience is also highly dependent on relationships with managers, and research pointed to a strong correlation between managerial skills and turnover. In addition, workers want opportunities to develop professionally, but they often perceive a lack of opportunities — pointing to the importance of investment in career progression and more effective communication of available programs and upskilling.

A Convenience Industry Action Plan

The convenience retail industry would benefit from a collaborative effort to address the needs of the frontline workforce and close the gap between potential employees’ current views of the industry and their ideas of an employer of choice. This report identifies key needs that emerged from the research and highlights solutions and actions that can be taken. Beyond individual retailer actions, the NCCRRC recommends that the industry pool resources to pursue game-changing solutions collectively in essential areas. These actions will transform access to the available labor pool and lead convenience retailing to be sustainably viewed more favorably as an employer of choice:

- Invest in employee safety through technology, analytics, and training

- Leverage government relations to remove regulatory barriers to employment and to toughen penalties for workplace violence in retail

- Invest in frontline training and development to expand the pipeline of talent and enhance long-term career opportunities across the industry

- Implement solutions that expand access to affordable, reliable transportationfor workers — both personal and public

- Leverage media to improve industry perceptions

Context and Objectives

Context

Convenience retailers are transforming their forecourt and in-store offerings to keep pace with changing customer demands, often increasing their need for a more skilled frontline workforce. At the same time, the nearly one trillion dollar industry — which employs more than 2.4 million frontline workers — faces unprecedented challenges in attracting, developing, and retaining these employees.1

In much of the US economy, employers have been engaging in fierce competition for labor, as the unemployment rate remained at or below 4% from January 2018 to February 2020, and again from December 2021 at least through the end of 2023.2 In addition, the surplus of job openings over job seekers rapidly widened from mid-2020, although there are signs that the gap may be closing. Moreover, some potential employees have opted out of fulltime employment in favor of working in “gig economy” jobs, such as ride-share driving and on-demand delivery, where they can be independent contractors with a high degree of flexibility and control over their schedules. Convenience retailers are therefore competing for a limited pool of job seekers, making it crucial for them to stand out as desirable employers.

Despite the labor environment improving slightly in 2023, hiring costs remain a challenge. Hiring a convenience store manager costs an average of $3,242, according to the NACS State of the Industry (SOI) Compensation Report of 2022 Data, compared to $1,633 in quick-service restaurants (QSR). The cost to hire a full-time associate averaged $1,196 that same year. When amplified by the high turnover rates in the industry, that number becomes increasingly significant. Additionally, the newly termed issue of employee ghosting (getting hired but never showing up to work) averaged 18.7% for full-time sales associates in 2022. Recruitment hurdles remain significant, and the search for talent will become more difficult without change.

Many convenience retailers have attempted to address labor challenges through wages: Hourly wages for store-level associates have increased by nearly 70% over the past decade. Despite this wage growth, retention rates have not significantly improved, turnover rates for store associates (full-time and part-time combined) averaged 141%, according to the NACS SOI Compensation Report of 2022 Data — an increase from 86% in 2013. Associate turnover has been over 100% since 2016. These figures highlight the need for more systematic approaches to address complex, industry-wide challenges.

The challenges — of labor scarcity, post-pandemic employee burnout, and diminished job satisfaction — have put a strain on the convenience retail industry’s operational efficiency. The NCCRRC research showed that these challenges are shared across the industry and therefore require industry-wide action. Addressing these issues must be a top priority, requiring a comprehensive reassessment of the industry’s most valuable asset: its people.

1 NACS State of the Industry Report, 2022

2 NACS State of the Industry Compensation Report of 2022 Data

Objectives

To tackle these structural challenges, the NCCRRC research delves into the root causes of the labor challenges and highlights the realities of convenience industry jobs as seen by both current and past frontline staff. The research provides key insights into the reasons potential employees may not see the convenience industry as an ideal place to work.

The findings highlight four significant areas with opportunities for improvement:

Building a robust talent pipeline

Fostering higher employee engagement

Addressing role disparities

Empowering career progression

Methodology and Inputs

The Coca‑Cola Retailing Research Council North America NACS (NCCRRC) hired Oliver Wyman and Mercer in 2023 to conduct the research for the Convenience Industry Action Plan. The research is based on three main sources:

- Qualitative frontline perspectives. Four focus groups were consulted with a total of 30 former convenience-store employees, quick-service restaurant employees, and gig workers. These participants shared their experiences and highlighted the key factors that influenced their employment decisions.

- Quantitative analysis of potential workforce. A survey was conducted of 45,205 US adults including a mix of current and former convenience employees, other frontline workers, and people not open to working in frontline roles. The survey aimed to understand workplace motivators, workers’ perceptions of the convenience industry, and the challenges they face. Unless otherwise cited, all numbers in this research and the Convenience Industry Action Plan come from this survey.

- Industry interviews. The insights and the Convenience Industry Action Plan include input from industry experts and executives representing NCCRRC organizations, as well as past research from NACS, Oliver Wyman, and Mercer on trends in convenience retail and frontline employment.

Unless otherwise cited, all figures and charts within this action plan are from the survey. All direct quotes are from the focus groups.

The Current State of Frontline Employment in Convenience Retail

The Talent Pipeline

There are numerous reasons why many people in the US workforce would not take a job in the convenience industry. The survey work explored the different drivers behind that decision.

Misconceptions and limited understanding of convenience store roles

Many hiring managers say that typical prospective employees are not aware of the depth and breadth of responsibilities of a frontline convenience store worker. They are not aware of the many elements required to successfully operate a store, such as inventory management, customer service, store hygiene, and foodservice. As a result, they do not know about all the skills that can be acquired through a job in convenience retail or the long-term career opportunities offered.

The pool of candidates

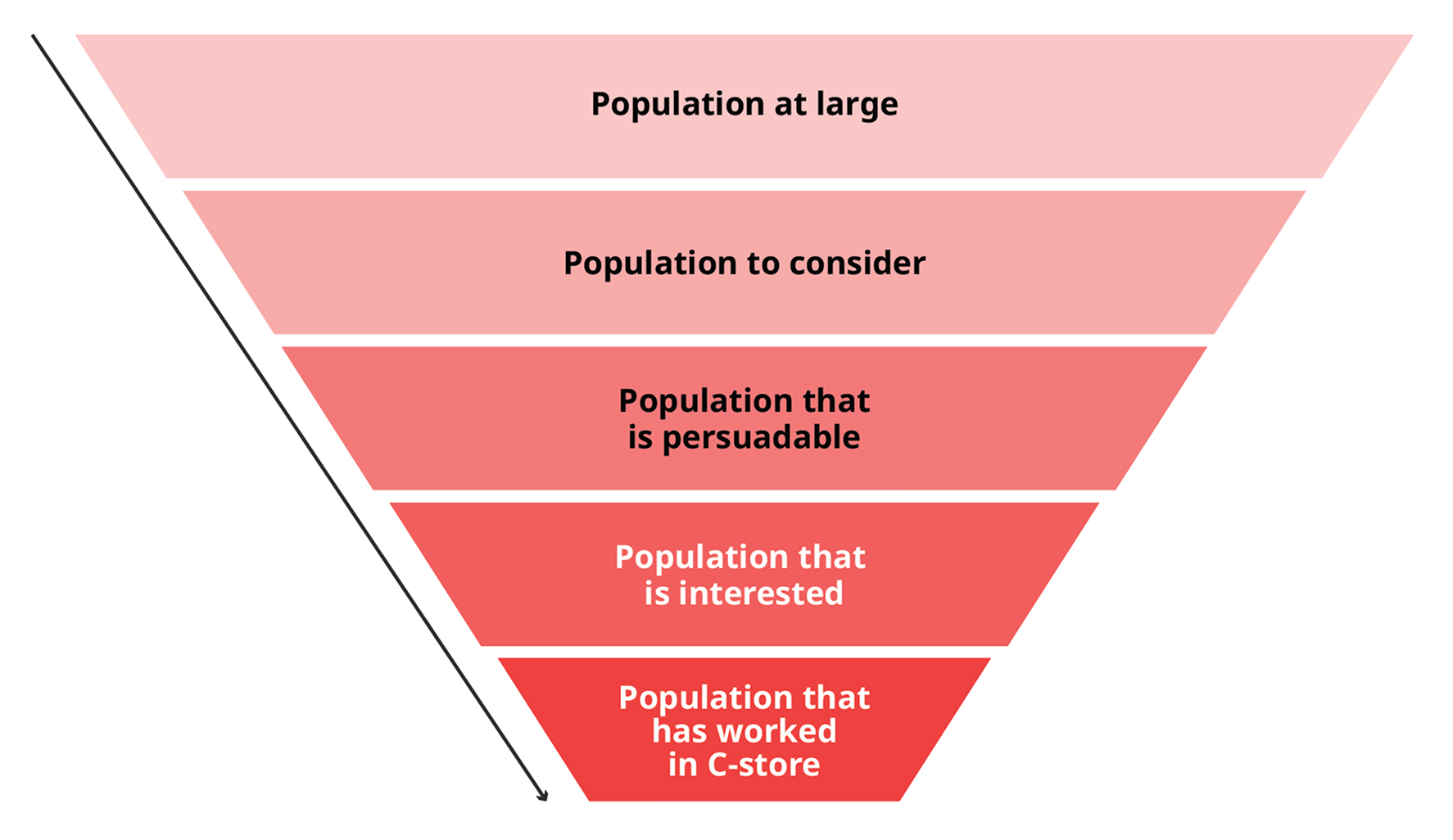

Potential employees are filtered out of convenience in several ways. Some would not consider a frontline role; some could not be persuaded; and some are not interested (Exhibit 1). There are two ways to improve the talent pipeline: bringing more prospective employees into the consideration set and improving the perceptions of those in this set.

Exhibit 1: C-Store addressable employment population pyramid

Exhibit 2: C-Store addressable employment population pyramid (%)

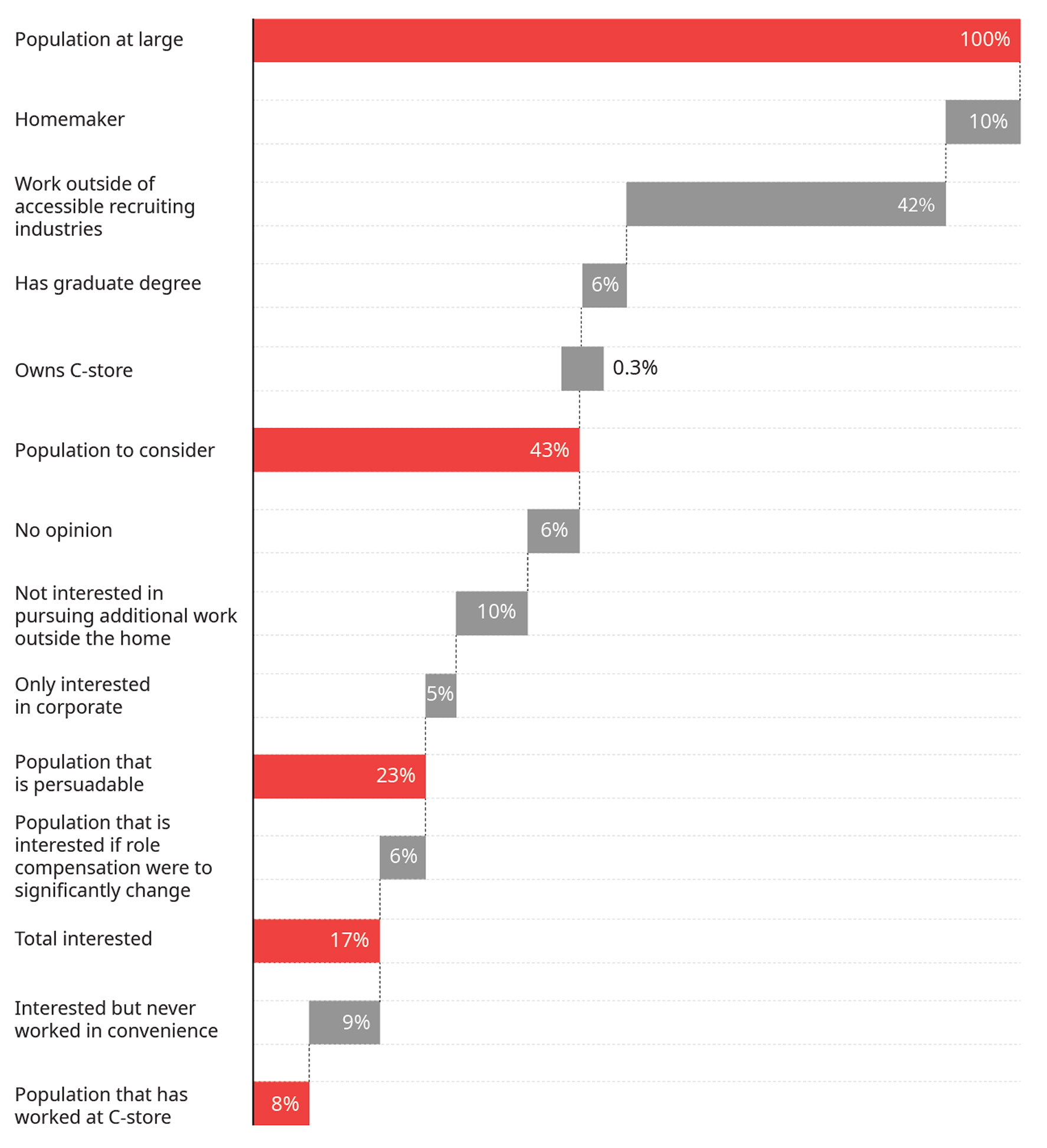

Over half of the population is outside the consideration set for convenience — because they are in jobs that NCCRRC members believe people would not quit to work in a convenience store; because they have advanced degrees; or because they are homemakers not interested in pursuing work outside the home (Exhibit 2). While 43% of the population is in the consideration set, only 23% of the population is seen as persuadable, and only 17% would be interested in frontline convenience roles without significant changes.

The survey results indicate that interested and persuadable people are predominantly younger, male, and more diverse than those who are not interested. They also have lower levels of education (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Sentiment towards convenience store employment

Interest in convenience store employment by gender, age, race, and education levels.

N=7,093

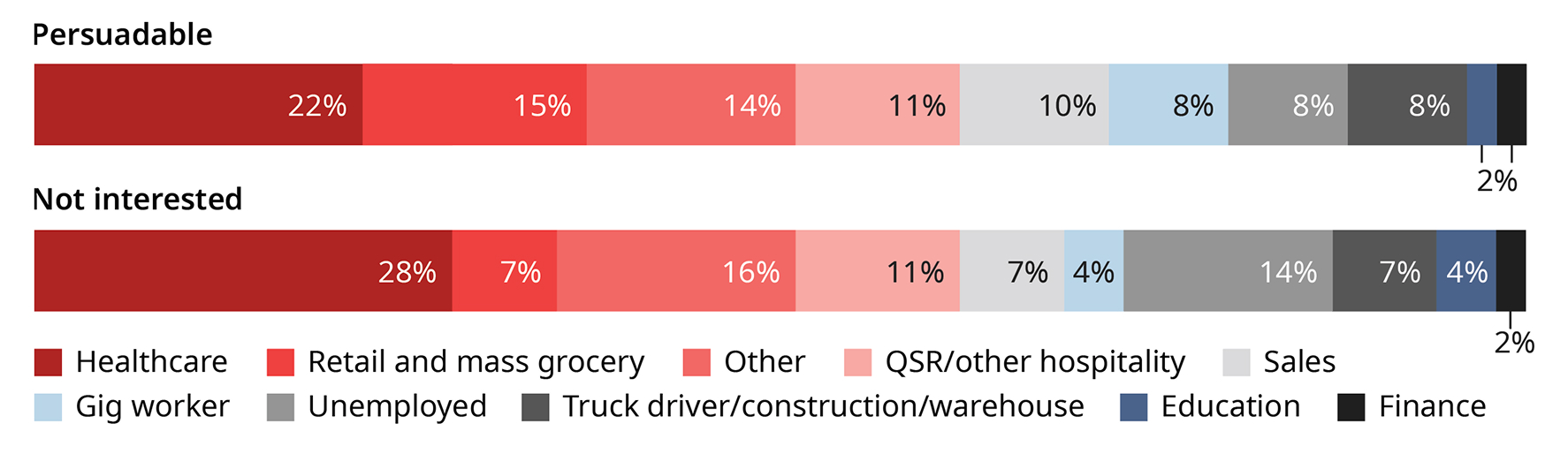

Larger groups of working-age people may be a great source of potential convenience store employees, even if they are less interested in convenience in percentage terms. Healthcare workers, for example, are less likely than the overall population of frontline workers to be interested in convenience (Exhibit 4). But, because there are so many of them, they make up the largest population of potentially interested employees.

Exhibit 4: Current industry of those persuadable and not interested

N=133

Overcoming negative perceptions and challenges

Apart from wages, perceptions of a lack of safety are the top deterrent for people who say they are not interested in working in convenience retail. Negative perceptions are shaped by personal experiences, second-hand accounts, and media. News coverage tends to emphasize instances of crime and reinforces the negative stereotypes of convenience-store jobs. For example, the top five search results for a late 2023 Google search on convenience stores were all crime-related. That contrasted sharply with results for searches of grocery stores, which tended to highlight weekly sales, new products, and new store locations.

Changing these deeply-ingrained perceptions will be challenging, but it is achievable through intentional and purposeful initiatives. These can be most effective when undertaken by individual companies, through both internal initiatives and brand-building campaigns and reinforced by an overarching industry message.

It is particularly worth noting that feelings about safety have a greater impact on the perceptions of current and potential female employees than on men: more than six in 10 female employees are worried that their store might be robbed (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Perception of Safety

Occurence or belief crime could occur by gender.

N=358

There is a perception gap: the share of people who believe pay is better in quick-service restaurants than in convenience is 30 percentage points higher among those who have never worked in the industry than among those who work in convenience today.

Inaccurate perceptions of pay are another reason many would not consider working in the convenience retail industry (Exhibit 6). While individual retailer pay varies, it is important to note that on average, compensation for frontline convenience employees is often in line with — or better than — quick-service restaurants and other frontline jobs.

Exhibit 6: Blockers to C-store employment

Top 3 reasons for not working in convenience.

N=4,824

Question asked: Which of these reasons best describe why you would not consider working in the convenience store industry?

Meeting Employee Expectations

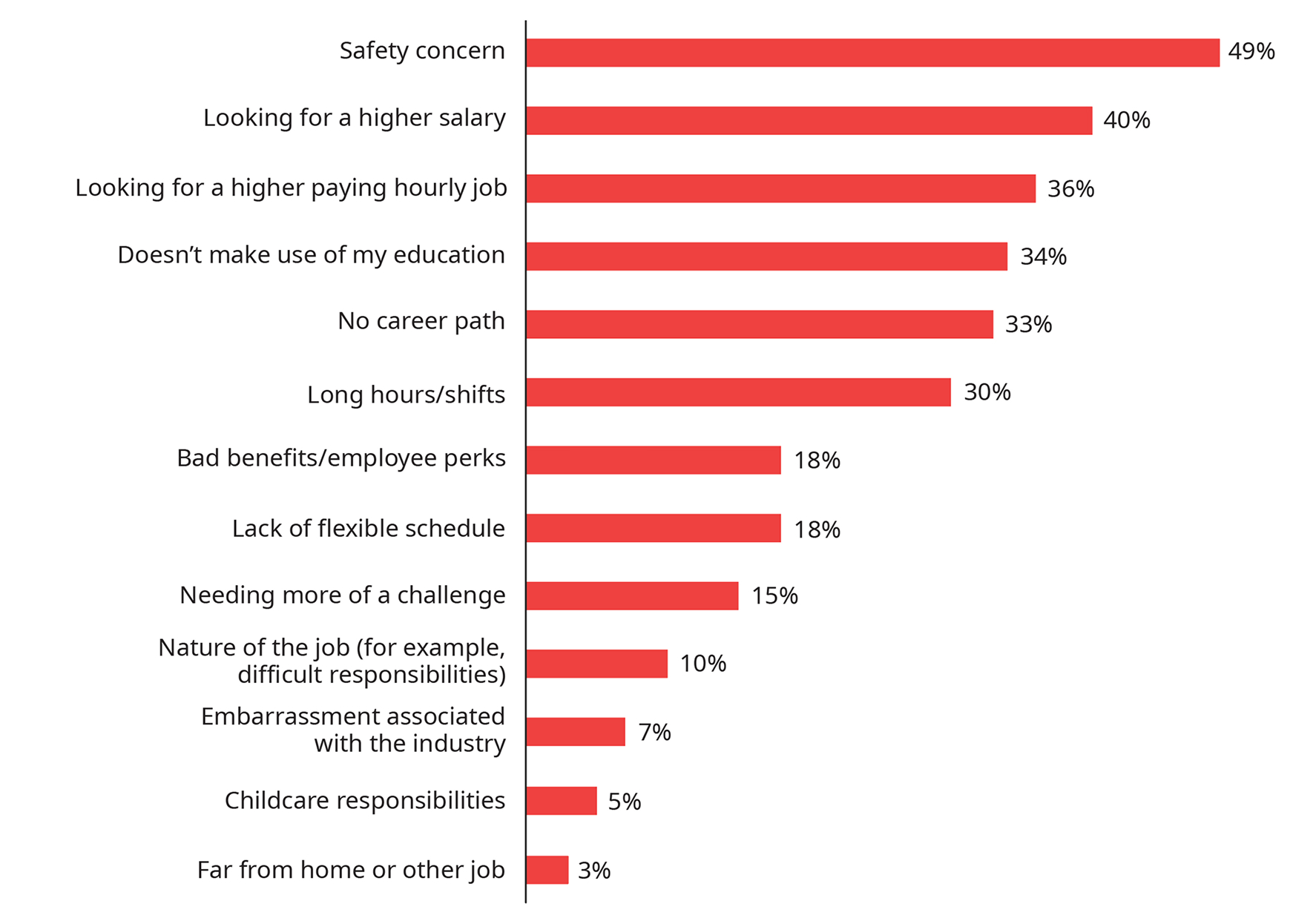

While not a new challenge, turnover in convenience retail is high and often a source of frustration and expense throughout the industry. Employees leave for many reasons (Exhibit 7). The most common is pay, but other common factors are a negative work environment and a lack of schedule flexibility.

Exhibit 7: Well-being factors that have led to C-store exit

Reasons for C-store exit, non-managers. N=331

49%

Looking for a higher salary

23%

Negative work environment and teamwork

21%

Safety concern

19%

Long hours/shifts

18%

Far from home/other job

17%

Continuing education

17%

Bad benefits/employee perks

16%

Poor relationship with manager

16%

Lack of flexible schedule

15%

Lack of recognition and appreciation from managers

The value of schedule flexibility

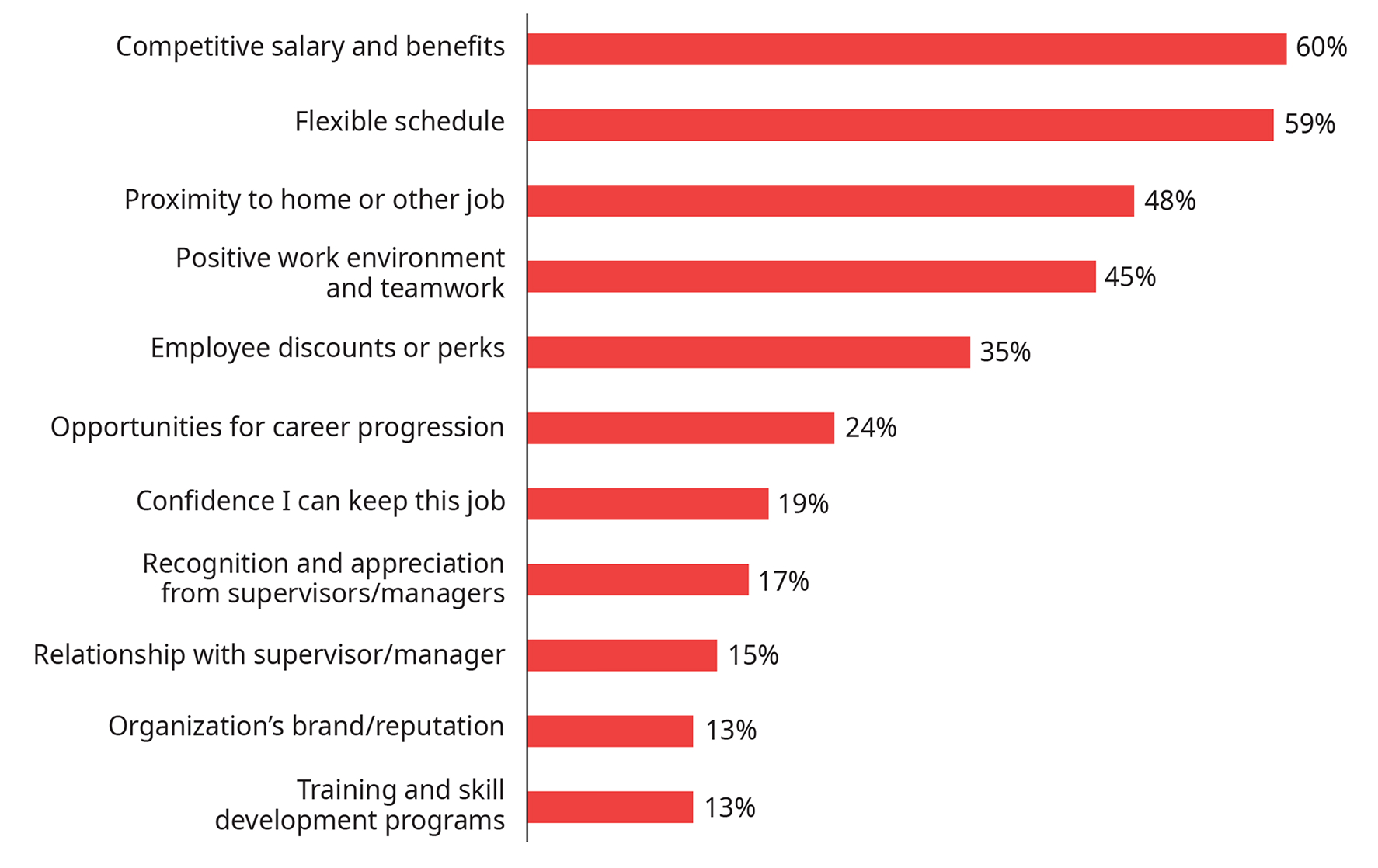

Current and potential employees are highly motivated by schedule flexibility (Exhibit 8). Among people persuadable to take a convenience retail job, six in 10 stated that a flexible schedule would motivate them to take a job. Gig work is perceived to offer significantly more flexibility than a frontline position in the convenience industry. However, gig work is not a major competitor for frontline employees: only one in nine former convenience store workers surveyed currently is employed as a gig worker as their primary source of income.

Exhibit 8: Motivators for those persuadable to convenience

Motivating factors to work in C-store. Percentage of respondents selecting factor in top 5.

N=141

Question asked: Which factors would motivate you most to work in a convenience store? (Select five factors)

Inaccessible transportation impacts workforce retention

More than in other industries, past and potential frontline convenience workers are challenged by access to available transportation and cite improved transportation access — or proximity of the workplace — as a reason they would choose to work in a convenience store. Nearly half (48%) of the persuadable population would work in convenience if the store were in close proximity to their home or other job (Exhibit 8).

Store managers are five times more likely than other frontline employees to recommend their job to a friend or family.

Role Disparities

The research highlighted a major difference between store managers and other frontline employees in perceptions of convenience retail as an employer of choice. It is essential to understand the challenges these perceptions create and to come up with meaningful solutions.

Managerial influence on employee satisfaction

Most managers in convenience retail today see the industry as an employer of choice. As well as being more satisfied with their own work, managers are also a major driver of frontline workers’ satisfaction.

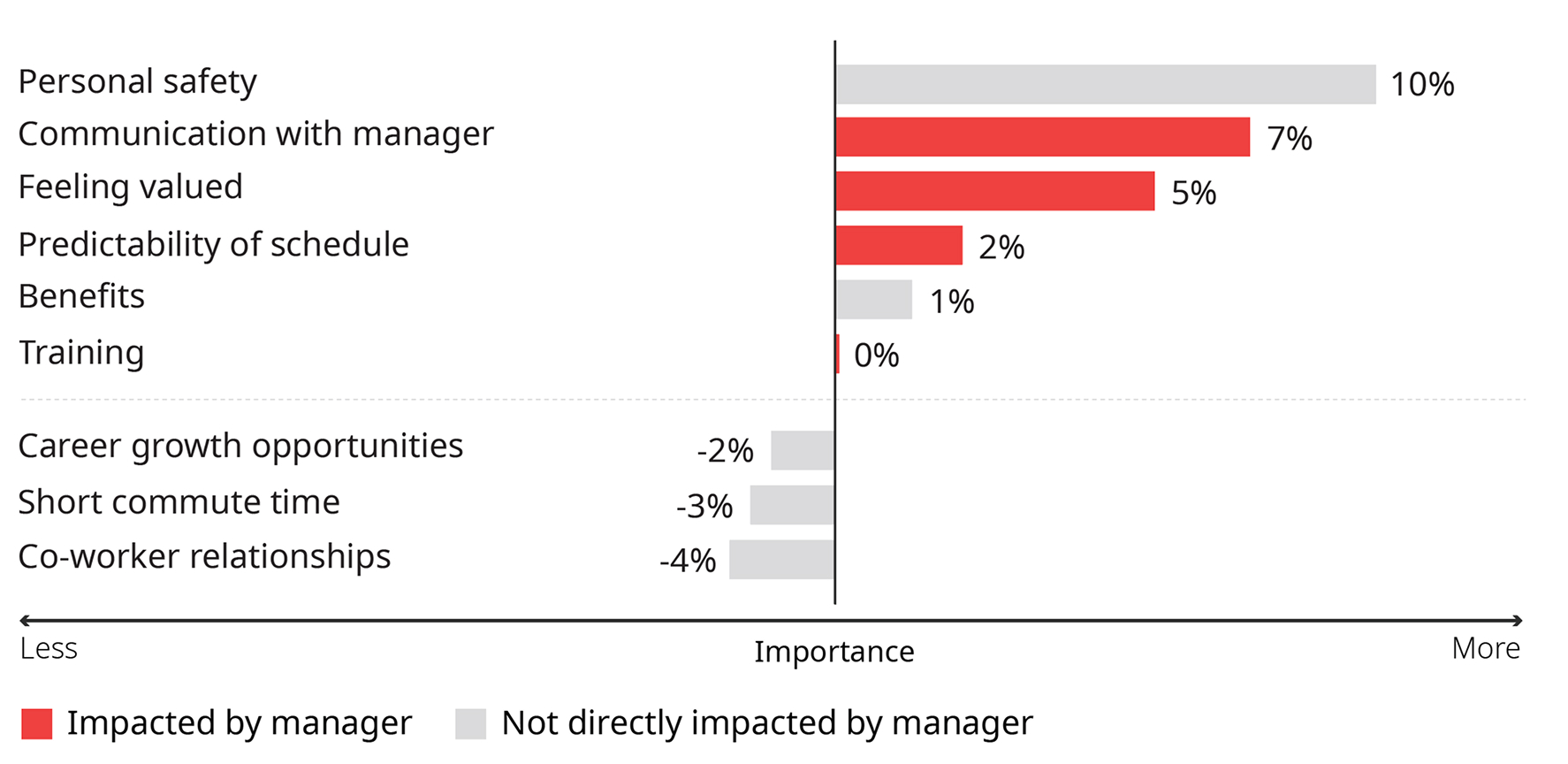

A seven-year longitudinal research paper by the Self Management Group on the manager-employee relationship identified a strong correlation between management turnover and employee turnover, highlighting the importance of management stability. Employees who had the same manager as when they started were retained at double the rate of others three years after being hired. If their hiring manager departed, nearly 50% of employees left the organization in the same calendar year.3 These results matched findings from our survey. Many of the factors which managers have more influence on are more important in driving employee satisfaction (Exhibit 9).

Managers serve as the face of the company for frontline employees and as a critical link between corporate programs and individual experiences. It is therefore essential to ensure the manager’s effectiveness in modeling and communicating corporate values, programs, and behaviors. Some employees believe that their manager filters good ideas and limits their ability to improve their day-to-day experience and contribution. Surprisingly, many of the survey respondents were unaware that the store they worked at was a part of a larger regional, national, or international organization while those at small chains sometimes thought the companies were much larger. When employees have no understanding of the corporate entity, an ineffective relationship with an individual manager can render corporate messaging silent.

3 “Management Turnover Drives Employee Turnover,” Self Management Group, 2017

Exhibit 9: Most factors important to employee satisfaction are directly impacted by managers

Relative importance to satisfaction. Percentage above/below average response for current C-store non-managers

N=361

Question asked: How important are these factors to your overall job satisfaction? Several factors that were not relevant were removed from this exhibit. Relative importance to satisfaction represents the difference between importance scoring (1–5) of each factor above/below the average of respondents’ scoring for all factors

The consequences of undervaluing workers

Lack of recognition and appreciation for non-managers can result in feelings of undervaluation and diminished morale. Fifteen percent of non-manager respondents to the survey identified such feelings as their main reason for leaving their job.

In their words

It's embarrassing for me because I have a master’s degree. People don't respect it; they respect you going to work from 9 to 5.

Former convenience store worker

Tennessee

We have an issue that comes up, [management] doesn’t do much about it. They say it’s employee first, but it’s really not.

Former convenience store worker

Iowa

Nowadays, you don't really get recognition for anything or even just a thank you from the manager.

Former convenience store worker

Maine

When managers show genuine appreciation for their team members, it creates a sense of belonging and loyalty. Employees who feel valued by their managers are motivated to perform at their best, are more likely to be satisfied at work, and are less likely to quit.

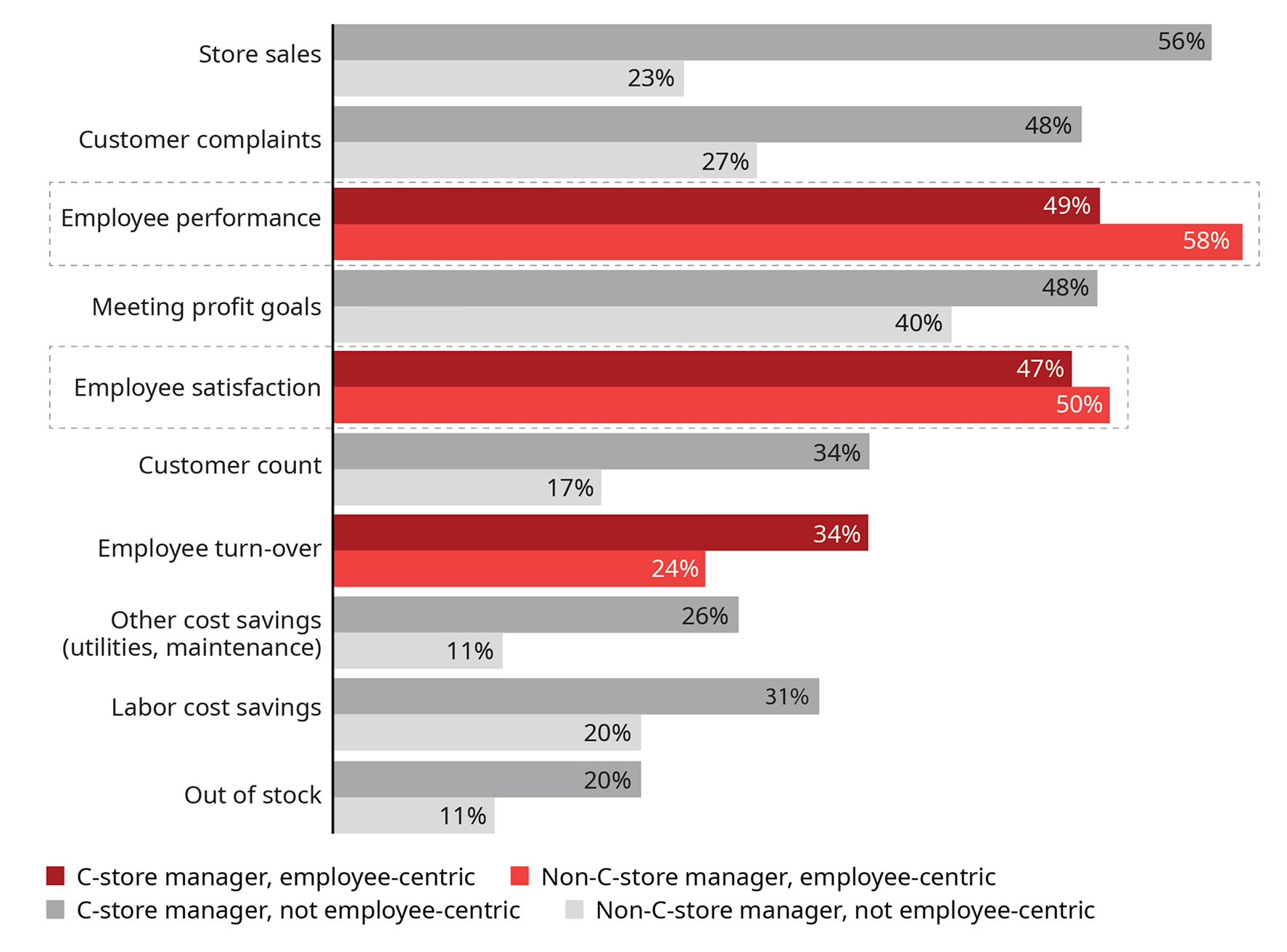

Redefining manager evaluation

The way managers are evaluated may contribute to non-managers’ perceptions. Managers in convenience are slightly less likely than those in other retail formats to be evaluated on how they manage their employees (Exhibit 10). Conversely, they are more likely than their peers to be evaluated on hard metrics such as store sales, number of customer complaints, and cost savings. The evaluation of managerial effectiveness can be expanded to measure performance in employee retention and satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and training completion.

Exhibit 10: C-store can place more focus on employee-centric KPIs

KPIs used in performance review. Percentage of C-store and non-C-store managers that are evaluated using respective KPIs

N=333

Questions asked: How is your performance evaluated? What KPIs?

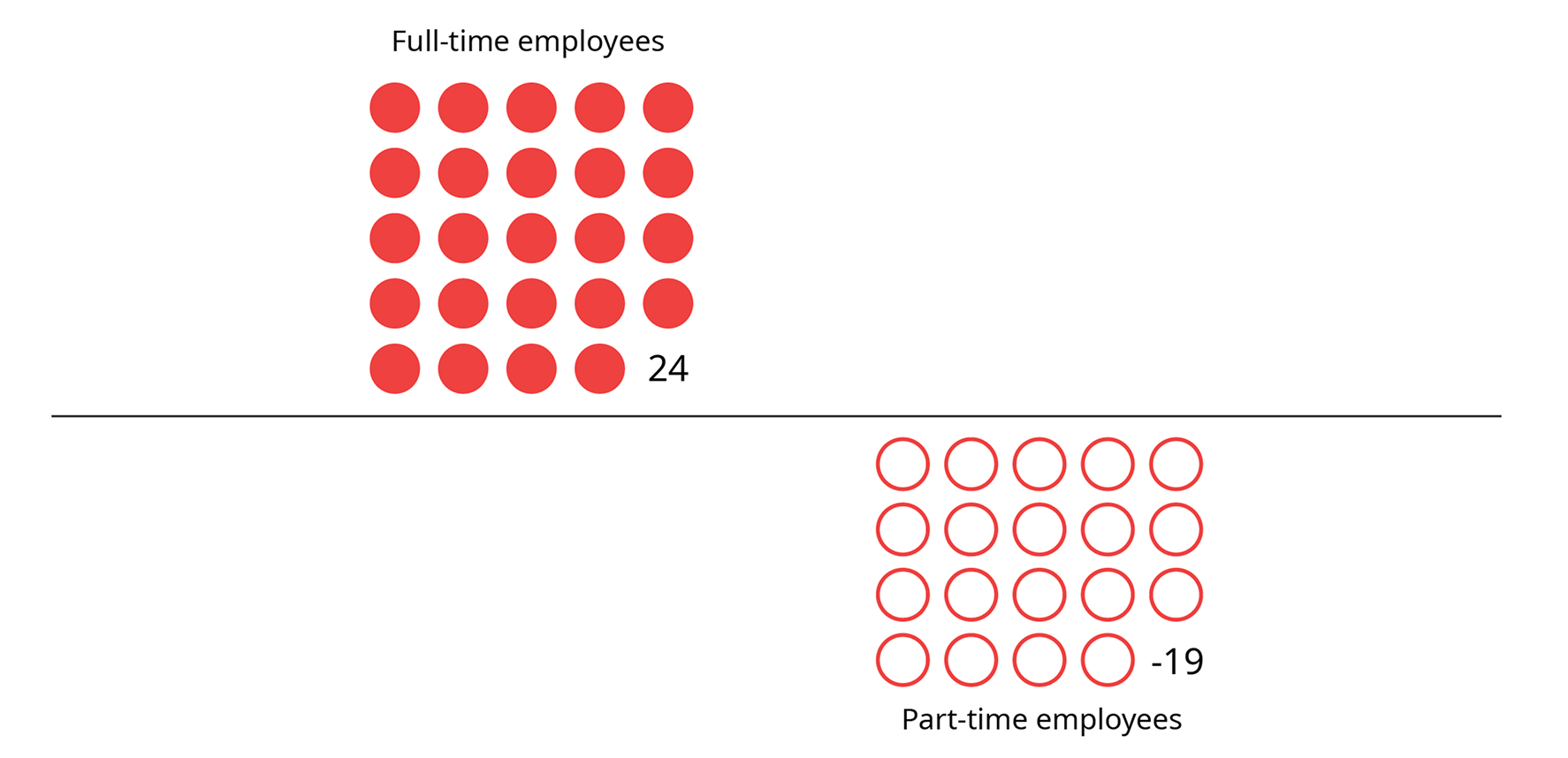

The divide between part-time and full-time employees

Full-time frontline employees have a significantly better perception of convenience jobs than their part-time colleagues. The net promoter score (NPS) — the likelihood that they would recommend working at a convenience store to a friend — is 43 points higher for full-time employees than it is for part-time workers (Exhibit 11). To improve their employee value propositions, individual retailers can look for ways to close some of the gaps — both financial and non-financial — between the experiences of full-time and part-time employees. Retailers may also consider adjusting the balance between full-time and part-time despite the direct costs given the reduction in spend required on re-hiring and re-training.

Exhibit 11: Full-time employees have a much higher NPS than part-time employees

Net promoter score (NPS) by employment status.

N=270

Question asked: How likely are you to recommend working at a convenience store to a friend? Please rate on a scale of 1 to 10 where 1=‘not likely at all’ and 10= ‘very likely’

Perceptions of Career Progression

Frontline workers often perceive a lack of career progression in convenience, and they cite this both as a barrier to entering the industry and a reason to leave it. Nearly 50% of former employees would consider ‘better career prospects’ as one of their top five potential motives to return to a frontline job in convenience if it were offered. However, one in three prospective employees cites the lack of a career path as a reason to not enter the sector.

1 in 3 cites no career path as one of their top 3 reasons for not working in convenience.

Question asked: Which of these reasons best describe why you would not consider working in the convenience store industry? (Rank top 3 reasons). N = 4,824

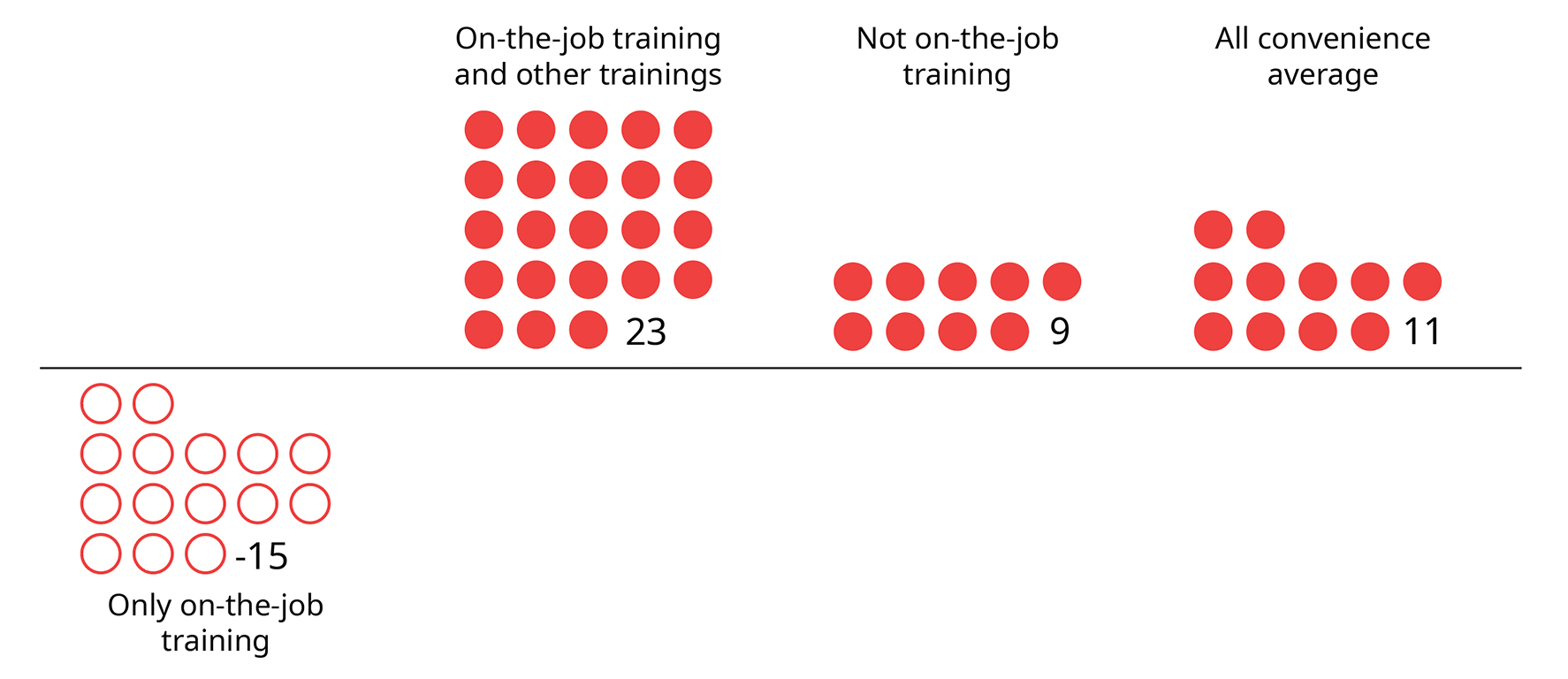

Employee development through training and education

Training plays an important role in career progression. The average net promoter score for workers who received both on-the-job and formal training was nearly three times higher than for those who received no on-the-job training, and significantly higher than for those who received only on-the-job training (Exhibit 12). Better training and experiences during onboarding prepare frontline workers more effectively to succeed in their jobs and also make them more likely to be satisfied. Training is especially important during the essential first months on the job. The industry averages a 36.5% turnover rate in the first 30 days for full-time associates, so over a third of full-time hourly associates don't make it to the second month on the job.4

4 2022 NACS State of the Industry Compensation Report

Exhibit 12: Mixture of training types lead to highest NPS for new hires

Net promoter score (NPS) by training type, C-Store non-managers only.

N=291

Questions asked: How likely are you to recommend working at a convenience store to a friend? Please rate on a scale of 1 to 10 where 1=‘not likely at all’ and 10=‘very likely’. Which of these training and onboarding activities did you receive when you started convenience work?

Career and educational development is important beyond the workplace. Convenience store workers have a strong desire to continue their education: 17% of non-managers in the survey left the job to continue education. That makes it important to develop opportunities for workers to access education or tuition benefits to advance their formal training outside employee-provided development.

A Convenience Industry Action Plan

There is no silver bullet to enhance the industry’s perception as an employer of choice. Reaching this goal requires efforts from both individual retailers and the industry as a whole.

No industry-wide campaign or program alone will improve access to talent in the absence of actions by all industry operators. That means individual retailers must continue to evaluate and improve their employee value proposition for both prospective and current frontline workers. However, the members of the Council believe that individual retailer action alone will not be sufficient to achieve the magnitude of impact required. The NCCRRC therefore thinks a coordinated, industry-wide effort is critical to achieving the goal of convenience retail being viewed as an employer of choice. Such a level of coordination would be new for the industry and would require both financial and time investment.

Invest in employee safety through training, technology and analytics

The safety of the convenience store worker is the top priority for any convenience operator. The need for efforts to enhance the safety of employees — and customers — by investing in emerging technology, training and data-driven solutions cannot be overemphasized:

Invest in employee safety to protect emotional safety

Equipping frontline employees to handle rude or aggressive customers could reduce the erosion of psychological safety felt by many frontline workers. Employees would benefit from both de-escalation skills and formalized procedures for bringing in help to address customer issues. Training programs on Civility, Respect and Dignity (CRD) and in conflict avoidance could include both positive engagement and diversion techniques to address anti-social behavior. Training in these skills could be an industry-wide asset.

Utilize technology to prevent major incidents

New technologies could improve retailers’ abilities to assess and address potential threats such as armed robberies and other forms of violence. The technologies include the scraping of both social media and proprietary data sources, as well as nascent artificial intelligence solutions designed to identify intent as people enter a store. Safeguards would be needed to implement these technologies in compliant and ethical ways. Deploying these technologies as an industry could create scale benefits that individual companies could not achieve. Smaller operators would benefit both from help in curating which technology solutions to deploy and from collectively negotiated rates. Larger operators would benefit from an industrywide scan of nascent technologies and the sharing of common practices.

Share more information systematically

The industry could share more information on workplace safety — for example, on common practices. Workplace safety discussions are often part of a broader conversation on asset protection. Separating the two should enable better outcomes in both areas. As retailers deploy experimental technology solutions, they can collaborate to measure their effectiveness and share how to deploy them in ways that are right for the customer experience and consistent with all legal guidelines.

Leverage government relations to remove regulatory barriers to employment and increase enforcement of anti-theft laws in retail

The industry should take steps at the local, state, and federal levels to reduce or eliminate the impediments for willing workers to enter and remain in the workforce.

Federal Level

Clarify labor regulations to tap into new labor pools

Working with government agencies to navigate the existing legal framework on foreign workers could increase the number able to work in the convenience industry. Executive policy might be the best focus for a government relations campaign, as it may be easier to influence than laws. However, the results may be more modest in terms of the number of employees who can take up a job and the duration of their potential employment. Examples include temporary visa programs for both one-year and seasonal work.

Manage rule definitions to maximize workers’ net income

While legislative changes could be helpful, understanding eligibility is a barrier in and of itself. No legislative action is required to gain a better understanding of the regulations on maximum income thresholds under which employees still remain eligible for various government benefits such as Social Security. Potential employees who understand these regulations may want to become employees if they understand they are not risking eligibility for benefits, while current employees may be more willing to stay on. For example, to receive food and security benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in 2023, an individual must make less than $1,580 in gross income per month.5 At the national average hourly wage of $13.76 for part-time convenience store employees, workers will still be eligible to receive this assistance if they work under 27 hours per week.6 Workers on Social Security cannot earn more than $1,860 in a month without risking benefits.7

5 USDA Food and Nutrition Service, 2023

6 NACS State of the Industry Compensation Report, 2022

7 Social Security Administration, Fact Sheet, 2024

State Level

Enact legislation to protect frontline employees

States can enact legislation that discourages criminal activity on the premises of convenience retailers, both at the pump and in the store. Laws such as Florida Statute 316.80 that specifically criminalize fuel theft and fraud reduce the threat of criminality on convenience store premises and can have a halo effect on other forms of lawfulness in stores. Legislation to protect frontline workers against violence can have a positive impact on workers’ perception of workplace safety.

Local Level

Enforce laws to reduce crime rates

Convenience retail would benefit from more consistent enforcement of anti-theft laws. Enforcement policies that emphasize the dollar threshold for theft neglect the impact it has on store associates. If addressing misperceptions of the impact of organized and individual retail crime leads to better enforcement, it will make employees and customers safer. There may also be opportunities to test technological solutions with retailers and law enforcement agencies to make enforcement more effective.

Maintain strong community ties

Many convenience retailers maintain strong relationships with law enforcement, both bringing them in-store with discounted or free food and/or beverages and doing outreach to community organizations, service providers, law enforcement and civic groups to strengthen connections and collaboration. Maintaining these strong community ties allows individual retailers to access the police, first-responder and social resources more effectively and can serve as a natural deterrent to safety incidents.

Invest in training and development to expand the pipeline of talent and enhance long-term career opportunities across the industry

Training and education are essential to developing talent and building a more robust pipeline of qualified workers. It is important for the industry to embrace opportunities to invest in training not only for current employees, but also for next-generation workers and workers looking to reskill for new careers.

Develop convenience store leaders

The NCCRRC recommends mirroring some of the industry-wide educational programming available to office-based employees for frontline workers. Operators must develop and provide access to a robust curriculum of operational, managerial, safety and customer-service skills that make frontline employees more effective and prepare them for roles of increasing responsibility. The gap between training provided in the first 90 days and when an employee is assigned to a new job role must be closed. There may be an opportunity for industry-wide solutions akin to the skill-based training programs that already exist for office-based employees. The industry could also look to adjacent industries like Chick-Fil-A Academy and McDonald’s Hamburger University for training curriculum that impart leadership development and managerial skills that transcend individual employers.

Establish common standards for transferable skills

Convenience retail, as an industry, can define the transferable skills frontline workers acquire to improve their perceptions of their prospects. Naming and standardizing the different elements of frontline work would more clearly demonstrate the potential career trajectory for people starting in frontline roles.

Develop high-school and vocational education curricula

A more ambitious step would be to introduce post-secondary education programs in convenience retail that mirror majors in hospitality and supply-chain management. These could raise the prestige of convenience work and enable employees who leave the industry to return in more senior roles. Perceptions of the industry could be heightened by exploring partnerships with local schools, community colleges, and vocational schools to develop leadership and customer service curricula that provide essential industry skills. Such efforts would expose next-generation workers to convenience-store career opportunities. Advanced curricula on industry-specific skills and certifications could also expand the pool of available labor.

Implement solutions that expand access to affordable, reliable transportation for workers — both personal and public

Research pointed to frontline convenience workers’ need for better access to transportation. When this is lacking, the geographic scope in which qualified workers can seek employment is limited. Transportation difficulties also contribute to worker absenteeism and voluntary termination. Providing transportation solutions can expand the industry’s labor pool.

Promote affordable vehicle ownership

Convenience retail could partner with commercial fleets or other organizations to make vehicles more affordable for frontline workers. Partners could include rental car agencies, companies with large passenger vehicle fleets, or even brand dealerships that provide access to pre-owned vehicles. Other potential actions could include enhancements to financing and insurance options by spreading risk across a much broader pool. Providing frontline workers with a pathway to own vehicles would address a major problem that many face, and serves to reinforce the convenience industry commitment to addressing its employees’ fundamental needs.

Partner with rideshare companies

Partnerships with rideshare or car rental companies could offer preferential rates to frontline workers when their primary means of transportation is temporarily unavailable and there is no suitable public transportation. Convenience store companies could also offer rideshare driver discounts or subscription programs for fuel, coffee, and other forecourt products as an incentive for heavily discounted rides.

Subsidize public transportation

Many companies already provide pre-tax travel benefits under the IRS provision for qualified transportation fringe, and some jurisdictions have even begun to require employers over a certain size to provide such benefits (the Illinois Transportation Benefits Program Act). However, these benefits are often limited to full-time employees. Employers in the convenience industry, which relies heavily on part-time staffing, should consider how they can ensure all associates can get to work reliably using public transportation where available. Extending transportation benefits (whether pre-tax, or post-tax through a restricted spend benefit card program) and/or partnering with or making bulk purchases from local public transit authorities are measures convenience employers might consider in this direction.

Leverage media to improve industry perceptions

With 86% of Americans living within ten miles of a convenience store and 43% living within one mile, the news and events that take place across our industry are integral to the communities we call home. To attract a vibrant workforce and prepare for the future, it is important to ensure that our industry is viewed positively.8

8 NACS, Convenience stores and their communities, 2024

Promote “good news” stories

Convenience retail must make a more concentrated effort to tell its positive stories more effectively. Despite the countless examples of the good that convenience store operators and their employees do in their communities, the proportion of these stories that are widely told is tiny in comparison to negative stories that characterize the industry. As a result, negative incidents dominate perceptions of convenience retail unfairly. Individual retailers can — and should — tell their own stories, but the industry must also collaborate to expand positive coverage of the good work we do every day. Building a campaign that recasts the industry in a more positive light is worth the investment required.

Celebrate employees as heroes

More widely, a PR campaign that reshapes how the public views convenience retailers — and thus encourages customers to behave differently — could improve everyday interactions. Campaigns focused on how customers act could come before the implementation of many of the other recommendations in this Convenience Industry Action Plan, and subsequent campaigns could build on the changes carried out. Individual retailers have had great success with campaigns encouraging kindness towards frontline workers or highlighting the individuals impacted by crime (whether an owner/operator or a local manager). A broader industry-wide campaign could expand coverage to a wider range of store operators and raise the image of the industry as a whole.

Formalize a framework for modern convenience

To guide individual retailers’ actions — in addition to collective actions — the industry would benefit from an explicit definition of what it means to act as an employer of choice. Defining “modern convenience” as a standard for both customers and employees could end some of the negative perceptions from the past. Developing such a badge of excellence would require significant investment in industry identity and consumer awareness. But it could obtain recognition for efforts by industry leaders to become employers of choice and to build on measures based on this Convenience Industry Action Plan.

Conclusion

The convenience industry has much to celebrate in how it has adapted to evolving consumer needs and business realities. For many frontline workers, their jobs serve as launchpads for successful careers within and beyond the industry. By enhancing the workplace experience and promoting the skills required for a successful frontline role, this Convenience Industry Action Plan is a solid foundation upon which the industry can attract and retain associates, unlocking a vibrant and sustainable labor force to propel future growth.

The council urges the industry to join together to prioritize, support and enable the execution of the strategies identified in this Convenience Industry Action Plan. Through aligned focus and support of all industry stakeholders — and with the leadership and guidance of NACS, we believe convenience retail has a significant opportunity to be viewed as an employer of choice.

About the Authors

NACS Coca‑Cola Retailing Research Council

Carlos Arenas

OXXO

Melanie Isbill

RaceTrac Petroleum, Inc.

Timothy Rupp

ReFuel

Jay Soupene

Casey’s General Stores

Michael Sansolo

Research Director

Henry Armour

NACS

Kevin Lewis

Circle K

Emily Sheetz

Sheetz

Lori Buss Stillman

NACS

Brian Ferguson

(formerly) Pilot Flying J

Chuck Maggelet

Maverik

Kevin Smartt

Kwik Chek Food Stores, Inc.

Rodrigo Zavala

Bach & Stern

Who We Are

The NACS Coca‑Cola Retailing Research Council is composed of convenience industry leaders from around the world. It conducts studies on issues that help retailers respond to the changing marketplace. The unique value of these studies rests with the fact that retailers define the objective and scope of each project and “own” the process through the release of the study and its dissemination to the broader retail community.

Our Mission

To identify big issues facing convenience retailers, do research that uncovers ways to deal with them, and then encourage retailers to use these new ideas to improve their business.

Oliver Wyman

Oliver Wyman is a global leader in management consulting. With offices in more than 70 cities across 30 countries, Oliver Wyman combines deep industry knowledge with specialized expertise in strategy, operations, risk management, and organization transformation. Oliver Wyman is a business of Marsh McLennan.

Mercer

Mercer is a global consulting firm that helps organizations and individuals navigate the complexities of the changing world of work and make informed decisions regarding their employees health, retirement, career and overall well-being. Mercer operates in more than 130 countries and serves clients across various industries. Mercer is a business of Marsh McLennan.